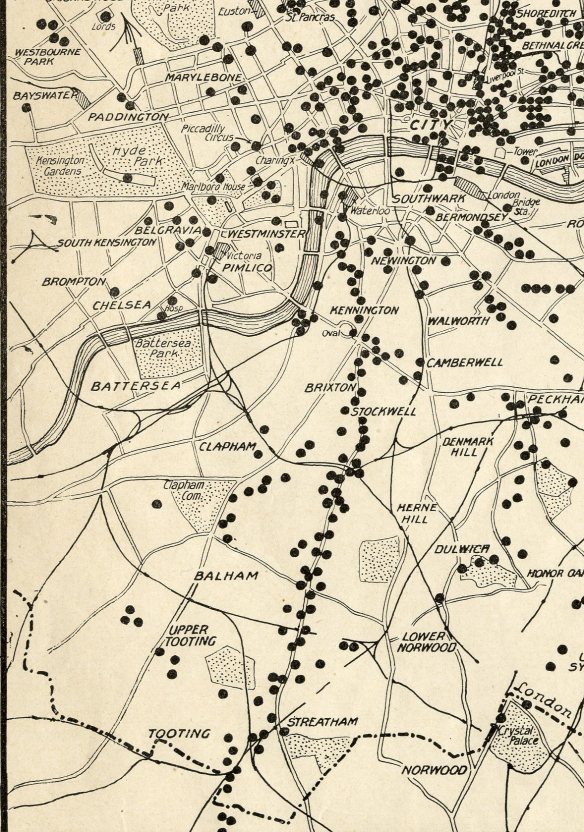

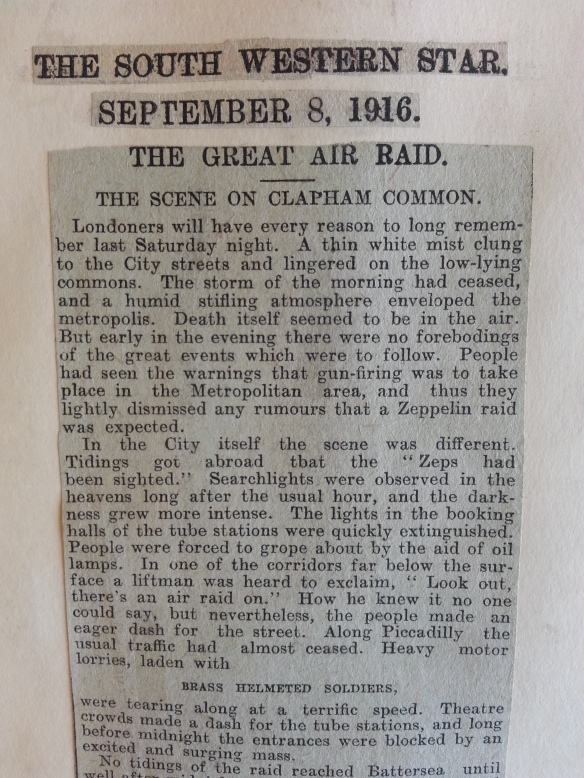

This title was the subheading of a lengthy article in the South London Press on 31st January 1919 (cont. 14th February 1919) detailing the zeppelin air raid of Saturday 23rd September 1916, which saw bombs rain down on South West London. It reports that the first bombs of the raid fell on Bromley-by-Bow shortly after midnight killing five people and injuring several others. Fifteen minutes later ‘the terrifying thunder of incendiary and explosive bombs aroused the inhabitants of Streatham, and then followed the terrible results of one of the most remarkable raids of the series – at all events as far as South London was concerned.’

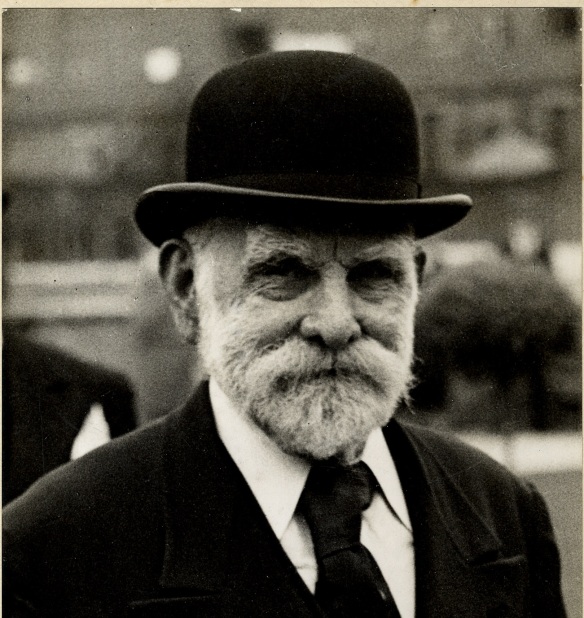

In an earlier post we told of how London had beefed up its air defences in the early part of 1916 and had successfully averted a zeppelin raid at the beginning of September. A few weeks later however, London was not so lucky and on this occasion the airships used flares to blanket the searchlights, putting the anti aircraft gunners at a disadvantage and enabling the airships to proceed on their deadly course. John Hook also reports in his booklet The Raids on Lambeth and Wandsworth, that the L31 zeppelin, commanded by Heinrich Mathy, was flying ‘unusually high and fast’ at an estimated 12,000 feet, crossing London from south to north and then making its escape.

Kapitanleutnant Heinrich Mathy / Imperial War Museums Collection / © IWM (Q 58566)

It is thought that Mathy directed the L31 zeppelin towards London by following the railway line from Eastbourne to London. After Mathy’s flares had dazzled the gunners at Croydon, the airship made its way towards Streatham Common station, dropping bombs on Mr. Tomlin’s vegetable garden at 30 Ellison Road along the way. Some of the railway tracks were then hit, followed by houses on Estreham Road opposite the station. A shop on Greyhound Lane had its windows blown in by an incendiary bomb which left a small crater in the pavement outside. Special Constables rushed to the scene and with the help of local residents began rescuing trapped and injured occupants of the bomb damaged buildings. The Red Cross treated nine casualties who were taken to Streatham Common station, where an emergency first aid post had been set up.

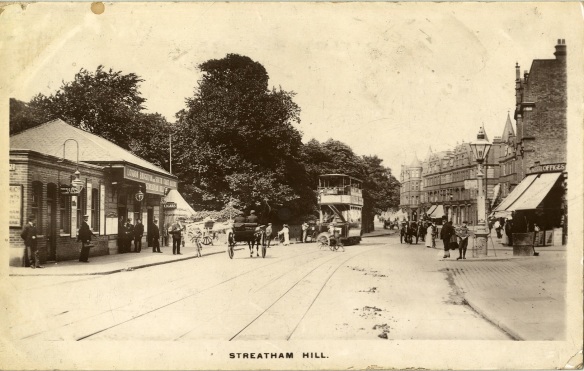

The zeppelin inflicted further damage along Gleneagle Road and Leigham Court Road, but according to at least one source ‘the worst incident of the raid occurred outside Streatham Hill Station.’ Streatham Hill Modern School stood on the junction of Streatham Hill and Sternhold Avenue, next to the station. A bomb exploded in the school’s garden, the blast from which killed four men outright who were on board a tramcar standing outside the station at the time. Another passenger died later from his wounds. The booking office and waiting rooms at Streatham Hill Station were damaged, as well as surrounding properties. Later, as morning dawned it was discovered that there was an unexploded bomb on the roof of Sainsbury’s opposite the station, which had to be removed to safety.

Streatham Hill c.1910 / Wandsworth Heritage Service Postcards collection

Bomb damage to a girls’ school near Streatham Hill station following the Zeppelin raid on the night of 23 – 24 September 1916 / Imperial War Museums Collections / © IWM (HO 99)

Further explosions erupted further along Streatham Hill, in Pendennis Road, Tierney Road and Telford Avenue, as the zeppelin progressed towards Brixton and on towards Central London. John W. Brown reports in his book Zeppelins Over Streatham: ‘During a period of less than 15 minutes, Heinrich Mathy had dropped a total of 32 bombs on Streatham, comprising 10 explosive and 22 incendiary devices. He had killed seven people and had seriously injured a further 27 in what was the worst night of destruction Streatham had ever known.’

Heinrich Mathy received military honours from the Kaiser for his efforts in penetrating London’s defences, but the L31’s reign was not to last. In a later raid on 1st October 1916 Mathy’s L31 zeppelin was shot down above Potters Bar, Hertfordshire killing Mathy and all 18 of his crew. They were buried in the local churchyard, where the crew of an earlier zeppelin crash had also been buried. In the 1960s their remains were removed to the German Cemetery at Cannock Chase, Staffordshire. Most of the metal from the wreckage of the L31 was used in the war effort. However, in the Potters Bar church of St. Mary the Virgin and All Saints can still be found an altar-cross made from metal taken from the wreck.

The South London Press is available on microfilm at Wandsworth Heritage Service

Publications held at Wandsworth Heritage Service:

The Air Raids on London during the 1914-1918 war: The Raids on Lambeth and Wandsworth – John Hook

Zeppelins over Streatham – John W. Brown

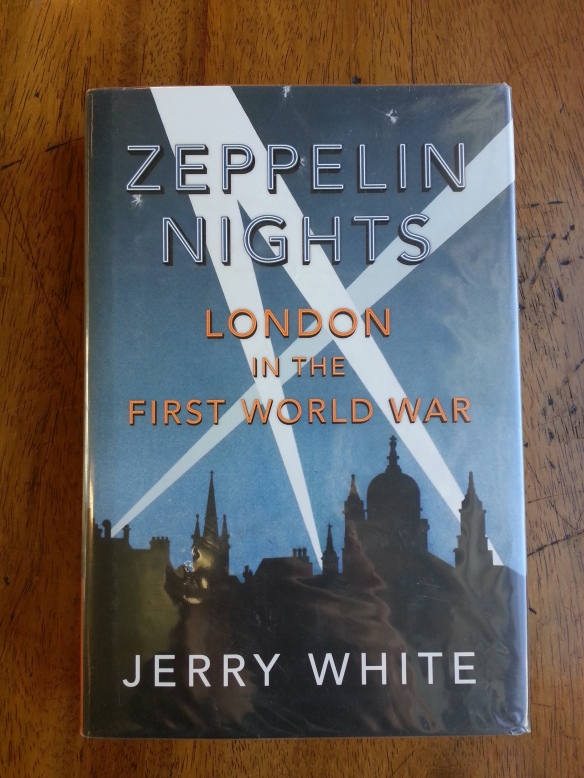

Zeppelin Nights: London in the First World War – Jerry White

The Twentieth Century: Streatham – Patrick Loobey & John W. Brown

Other sources:

St. Mary’s Church, Potters Bar website

Hellfire Corner – Heinrich Mathy and Zeppelin L31 at Potters Bar