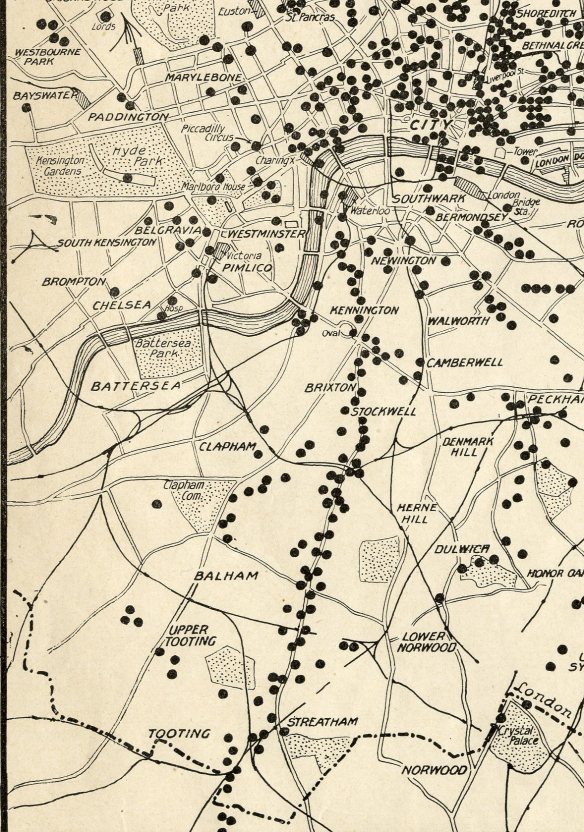

Many people are surprised to hear that air raids over London were not exclusive to the Second World War, and that in fact the First World War produced its fair share of nightly terror too. Of course, the scale of the bombing during the First World War did not equal that of the Second World War, but it was fairly significant, especially in the East End. South West London also had its fair share of attacks. John Hook lists 29 raids on Lambeth and Wandsworth between May 1915 and May 1918 in an extract of his book They Come! They Come! This map of the Wandsworth area is a detail from a larger map of London plotting the positions of the bombs that fell, published by the Daily Mail in 1919.

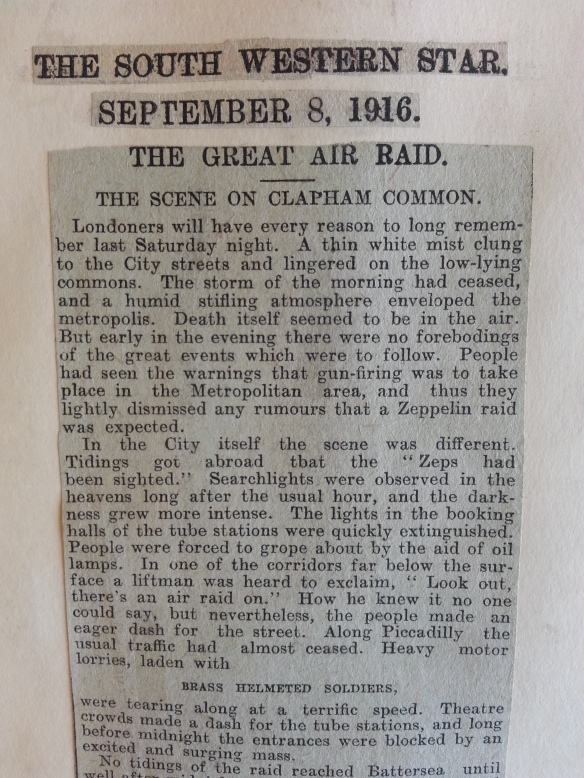

The South Western Star reported on an unsuccessful zeppelin air raid that took place on the night of 2nd September 1916. The journalist seems to relish the excitement in his reporting of the event, setting the scene as though he is writing a suspense novel.

He goes on to report that although by late evening people in central London were panicking and trying to get home because of the imminent zeppelin raid, ‘no tidings of the raid reached Battersea until well after midnight.’ Even then, he insinuates that the warnings were largely ignored and ‘like the wise people they are, the inhabitants of Battersea went to bed, not willing to lose the prospect of a good night’s rest.’ When gunfire disturbed their sleep in the early hours of the morning, it is reported that despite warnings to stay inside, hordes of people hurried outdoors to see what was going on. If this was indeed the case, it implies that this was a novelty and hadn’t been experienced locally up to that point, otherwise surely people would have recognised the danger and heeded the warnings not to venture out. However, it appears that those living in the vicinity of Clapham Common headed there in order to get as clear a view as they could of the night sky, and were rewarded with a searchlight display followed by a clear view to the north of ‘the ribbon-like form of a Zeppelin.’ They then watched as the zeppelin was engulfed in flame and slowly fell to earth. It was reported that ‘the light in the sky was brighter than any that Londoners had seen before, and a red glare quickly spread over the Common.’

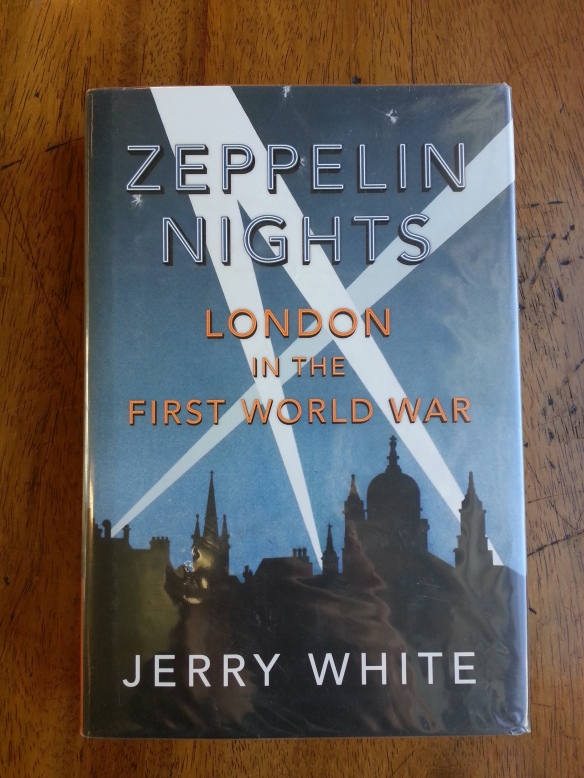

Jerry White’s book Zeppelin Nights gives an insight into the lead up to this thwarted air raid on 2nd September. In February 1916, there had been what he describes as an ‘ill-tempered debate’ in the House of Commons during which Lloyd George admitted Britain had been ‘very remiss’ in its neglect of air defence. During the next six months London reorganised its home defence squadron, attained more guns and searchlights and achieved better coordination. The public of course were unaware of these additional precautions, so nightly blackouts and unease continued during the summer months of 1916 even though there was a lull in zeppelin attacks. This had ended just a week before the raid I have been describing, with a raid by twelve airships on South East London which was largely unsuccessful. By the time this was followed up with the raid of 2nd September, the London defences were ready. These consisted of sixteen zeppelins, not one of which managed to hit their London targets. White writes: ‘Lieutenant W. Leefe Robinson of 39 Squadron at Sutton’s Farm achieved the first victory of London’s air war by bringing down around 2.30am SL11, a wooden airship, which fell in flames close to the village of Cuffley in Hertfordshire.’ It is approximately 30 miles from Clapham Common to Cuffley, so whether the crowd there would actually have seen the zeppelin’s demise as reported is open for discussion.

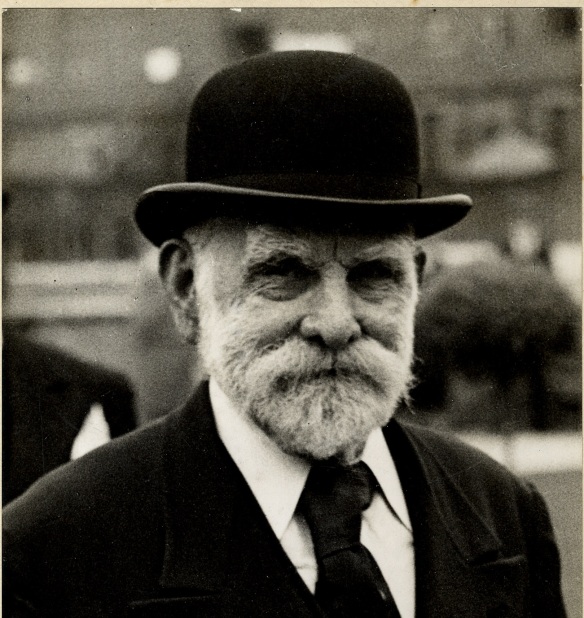

A cheer reportedly went up on Clapham Common as the crowd ‘gave way to one heartfelt cry of relief and triumph.’ 200 special constables and nurses had been standing by at Lavender Hill police station, but were dismissed when the danger had passed without need of their services. It is reported that ‘shortly after the Zeppelin had been destroyed, each man instinctively bared his head, and the National Anthem was sung.’ This after all was a visible sign of the allies striking a blow to the enemy, which must have stirred up everyone’s patriotism. John Burns was among the crowd on Clapham Common watching the spectacle that night. He seems to have approved of the measures that had been taken to improve London’s air defences, reportedly saying to some soldiers: “We are all right in London. Our defences are perfect. We have only lost a little over 400 lives after two years of war – not equal to one day’s casualties at the front.”

Unfortunately it wasn’t long until the German military regrouped and launched another airship attack on London, this time managing to break through London’s ‘perfect’ defences and striking a blow on South West London.

The South Western Star is available on microfilm.

Publications mentioned available from Wandsworth Libraries.