April’s edition of the Gazette of the 3rd London General Hospital covers the usual wide range of subjects, including noting that the magazine was now six months old and talking about its success. Some rivalry creeps in here, as it refers to one of their artists being sent there and “not to one of the other hospitals with whose magazines ours is in such pleasant rivalry”. The Gazette benefitted from a group of artists who had joined up as hospital orderlies – some of whom this blog has covered before, such as C RW Nevinson, but for this issue also included Australian artist Private Vernon Lorimer, who was a patient. The editors were pleased to have reached six months, as a voluntary endeavour often dried up after the first two or three, and felt that the Gazette “was never more alive than it is to-day” – although they did hope for the end of the Gazette when the war itself ended.

There were several articles about the nursing staff, as there often were, this edition including a photograph of Queen Amelie of Portugal, who was one of the nurses. Although she mainly lived in France after Portugal became a republic, she came to the 3rd London General Hospital to help with the wounded, “performing the ordinary duties of a probationer, going to her ward on arrival, and leaving when her duties were finished”. Few photographs of her at work existed, as she preferred to focus on what she was doing and not the press – the photographs in the Gazette were presumably taken purely because it was the hospital’s own magazine.

Nursing staff contributed their own articles to the magazine, including one about the first Zeppelin raid. It’s not clear if it refers to the first ever Zeppelin raid over London, or the first one which crossed over the hospital, but it does include an anecdote about a sister who sprang out of bed, dressed in perfect uniform at speed and disappeared to the wards, muttering: “let me die with my men”.

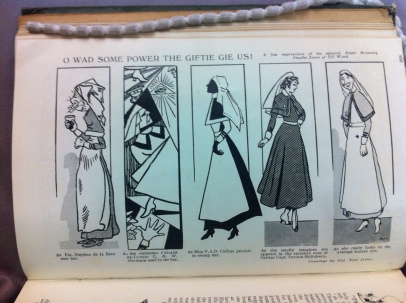

The nurses and artists were also the subject of an illustration by Corporal Irving, showing one nurse in the style of the various artists. Left to right, those are: Stephen de la Bere; C R W Nevinson; Miss VAD Collins; patient Captain Tomkin McRoberts; “as she really looks to the average human eye”.